At the age of 13, Susan Pollack – now a retired grandmother living in north London – was taken from her home in rural Hungary, loaded into a cattle truck and transported by rail through German-occupied Poland.

She and her family were told they were going to be resettled. The journey took six days and some in the truck died on the way.

“There was some straw on the floor,” she told me. “It was dark, it was cold, it was so hostile. And hardly any space for sitting down. There was a lot of crying, lots of children. And we were trapped. Doors were shut, we knew this was not going to be any resettlement but we had no imagination of course of what was to come.”

The doors opened at Auschwitz.

There, on the railway platform, Nazi officers separated those chosen to live and work from those sent immediately to die.

Susan lied about her age. A prisoner on the platform whispered to her that she should say she was 15. It saved her life, but her mother was sent immediately to the gas chamber.

“There were no hugs, no kisses, no embrace. My mum was just pushed away with the other women and children. The dehumanisation began immediately. I didn’t cry, it was as though I’d lost all my emotions.”

Active collaboration

Soviet forces entered Auschwitz on 27 January, 1945.

The Nazis had abandoned the camp days earlier, leaving much of it intact. More than a million people, mostly Jews – but Poles, Roma and political prisoners as well – had been murdered there.

Those railway lines – which can be still seen at Auschwitz-Birkenau today – extended to almost every corner of Europe.

The Holocaust was not a solely German enterprise. It required the active collaboration of Norwegian civil servants, French police and Ukrainian paramilitaries. Every occupied country in Europe had its enthusiastic participants.

After 1945, a great silence fell across the continent.

The Jews who survived found that the world beyond the perimeter wire of the camps did not much want to know their story.

The Jews who survived found that the world beyond the perimeter wire of the camps did not much want to know their story.

It was only in the 1960s that popular consciousness began to catch up with the crime perpetrated against an entire people.

Holocaust denial persists. The internet is full of claims that the destruction of the Jews never happened.

“Sometimes they want to call themselves revisionist historians,” says Pawel Sawicki, who works at the Auschwitz site, which now attracts two million visitors a year. “But they are not. They hate others. This is anti-Semitism.”

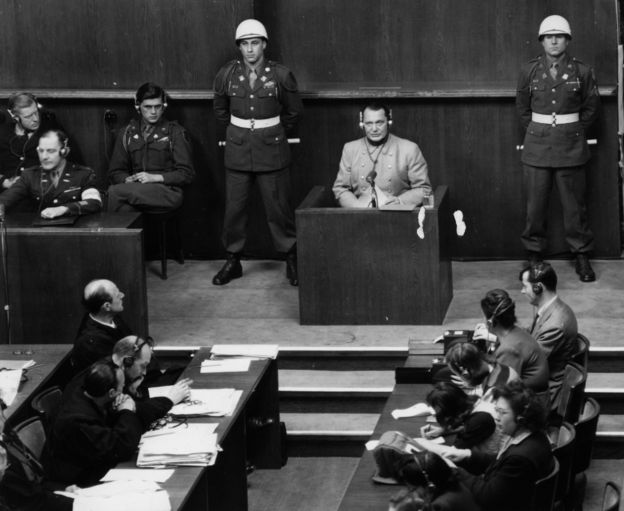

Judicial legacy

At the Nuremberg trials after the war, leading Nazis were held accountable for the state-sponsored crimes that had been committed in Germany and German-occupied territories. For the first time, two new terms entered the grim lexicon of wartime atrocity – crimes against humanity and genocide.

This is the Nazis’ judicial legacy – that from 1945, sovereign states no longer had legal carte blanche to treat their own citizens as they pleased.

“That’s the amazing, revolutionary, remarkable change that happened in 1945,” says Philippe Sands, an international human rights lawyer who has worked extensively on war crimes prosecutions.

“Before 1945, if a state wished to kill half its population, or torture or maim or disappear, there was no rule of international law that said you couldn’t do that. The change that occurred in 1945 – as we know very sadly – has not prevented horrors from taking place.

Near the blockhouses where Auschwitz prisoners were housed, there is a large open trench about the size and shape of a swimming pool.

During the war it was filled with water. Why? It was required by the camp’s fire insurance policy.

There is something grotesquely chilling about this – that a camp whose purpose was mass extermination would, at the same time, concern itself with sensible precaution and compliance with insurance law. And the company that insured the camp is still trading. There is a warning in this to posterity – to us, here today.

As the UK marks Holocaust Memorial Day, Mrs Pollack issues a stark warning about the importance of learning the lessons from history.

“We’re not talking about barbarians,” says Mrs Pollack. “We’re not talking about primitive society.

“The Germans were well-advanced, educated, progressive. Maybe civilization is just veneer-thin. We all need to be very careful about any hate-propaganda.

“This is very important. It starts as a small stream, but then it has the potential to erupt – and when it does, it’s too late to stop it.”

BBC